Still Trying Harder

By Mary Warlick on Feb 22, 2012

Paula Green was always a good writer, and a friend suggested she try the advertising business. “I’m not even sure I knew what that was,” she admitted. But she found her way, working as so many women have, first taking a job as a secretary and then taking on a myriad of tasks, including writing promotional copy and creating layouts. Like many aspiring copywriters, Paula pieced her early career together with a series of positions, first at Fawcett Publications, which handled magazines such as TRUE and Family Day. At Fawcett she was promoted to manager and soon after, she landed a job in the promotions department at Grey Advertising. It was her good fortune to land at Grey, because it was there she met some of the players whom Bill Bernbach would later invite to join him when he started his new agency.

As a young writer, she was sharp and absorbed everything in the business. And when she saw the startling new print work for Polaroid and Ohrbach’s coming out of this young agency, twenty-nine year Paula Green knew Doyle Dane Bernbach was where she wanted to work. She started as a copywriter there in 1956, hired by the late, great Phyllis Robinson.

It was a special time and a special place—a unique place because the people at the top were unique. Paula has remarked that yes, there was a lot of freedom, but also a lot of discipline. You were expected to do good work, you self-edited and always asked yourself, “Where are the holes?” before presenting a campaign to Bill Bernbach.

Green thrived in this highly charged atmosphere of young, smart writers and art directors. They understood they were making a new kind of advertising, a new way to communicate. For the next twelve years, she worked with some of the greatest art directors in the business—Helmut Krone, Bob Gage and Bill Taubin. Where Gage was spontaneous and effusive, Krone was challenging, at best, taking hours to “squeeze out the essential idea, the core, the exact kernel.” When Helmut finally put the type down, it was as though it were engraved in stone. Helmut acknowledged later in life that the Avis campaign was his all time favorite, and Paula readily admits it was hers as well.

Both Paula and Helmut were on the original team that met with Robert Townsend, the chief executive officer of Avis in 1963. The campaign they created together is one of the iconic benchmarks in the Bernbach portfolio. Everyone at Avis wore “We Try Harder” buttons, from the counter attendants to the garage staff, creating a new attitude for the company and moving their balance sheet from red to black. Green’s line, “We Try Harder,” tapped into America’s penchant for rooting for the underdog. She also invented the ammunition to support the case: We can’t afford dirty ashtrays, unwashed cars and nothing less than heaters that heat, defrosters that defrost.

In the 1960s, before there was The One Club or the One Show, there was the Advertising Writers Association of New York, and they gave out Gold Key awards. Paula took home one of the very first Gold Keys awarded for her campaign for Goodman’s Noodles. And she didn’t have to crawl out on a window ledge and threaten to jump in order to sell her work to the client. In 1964 her campaign for Avis, “We Try Harder,” was awarded one of only 15 Gold Keys given that year. Helmut Krone often groused that the Art Directors Club did not award him a cube that year. But that was before the One Show.

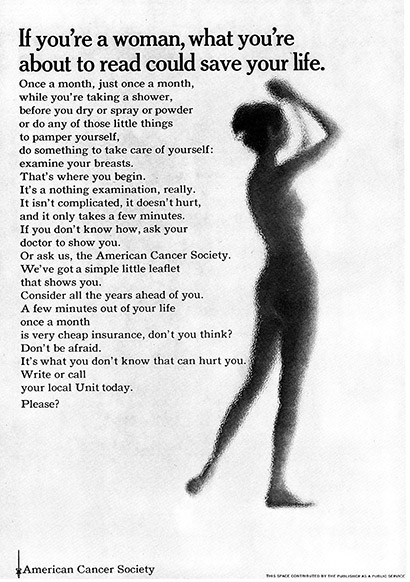

The year 1969 turned out to be hugely important for Paula. Both her peers and clients recognized her work, and the young woman from Hollywood who “tried harder” was on top of the world. She took up the gauntlet that Bill Bernbach advocated—use your talents for causes you believe in. Paula approached the American Cancer Society with a commercial about self-examination for early detection breast cancer. She felt it was crucial to make information available on television and to bring to the public an issue no one was talking about. It is hard to imagine today, with our evening news programs inundated with remedies for erectile dysfunction and the dangers of erections lasting more than four hours, that the American Cancer Society had an uphill battle to get this spot cleared by the networks because of the word “breasts.” Paula was brave and stood by her work and the line, “It’s what you don’t know that can hurt you.” The ACS aired the commercial and the response was immediate. The switchboards were overloaded with response, and the commercial is credited with saving scores of lives of women who called the ACS hotline and were discovered, in fact, to have tumors after their initial examination.

It was also in 1969 that Paula Green left Doyle Dane Bernbach and launched her own agency, winning clients like The New York Times, Ms. Magazine and Subaru.

Probably one of her best-known campaigns, and one, which has become part of American cultural history, was the song for the International Ladies Garment Workers Union. Paula wrote the lyrics for the song, “Look for the Union Label” with music by Malcolm Dodd, and created a commercial featuring real union members. Paula was actually referencing an earlier authentic source in the union’s history of workers singing an upbeat call to arms. Union members—sewing machine operators, basters and cutters—had staged the Broadway revue, Pins and Needles, which opened in 1937. “Look for the Union Label” struck a chord in people’s minds—it made people proud and spoke with a sense of honesty about the value of the work ethic. Long before the lightning speed of viral media, the song carried on and withstood some hilarious parodies on Saturday Night Live, South Park and the Carol Burnett Show.

Reflecting on the campaign and its success, Green acknowledged that the “Union Label” song had been a good try, but ultimately a “whistle in the wind” as manufacturing job losses continued and foreign imports increased.

Paula Green’s induction to the Creative Hall of Fame celebrates a lifetime legacy for honest straightforward copywriting, wit and dignity. The girl from Hollywood who tried harder indeed enjoyed success, both in her professional life and in a strong family life with husband John and son Joel.

Related